In 1866, an Act of Congress created six all-black peacetime regiments, later consolidated into four –– the 9th and 10th Cavalry, and the 24th and 25th Infantry –– who became known as “The Buffalo Soldiers.” There are differing theories regarding the origin of this nickname. One is that the Plains Indians who fought the Buffalo Soldiers thought that their dark, curly hair resembled the fur of the buffalo. Another is that their bravery and ferocity in battle reminded the Indians of the way buffalo fought. Whatever the reason, the soldiers considered the name high praise, as buffalo were deeply respected by the Native peoples of the Great Plains. And eventually, the image of a buffalo became part of the 10th Cavalry’s regimental crest.

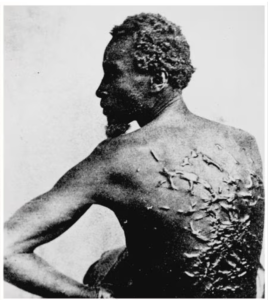

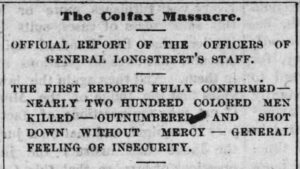

Initially, the Buffalo Soldier regiments were commanded by whites, and African-American troops often faced extreme racial prejudice from the Army establishment. Many officers, including George Armstrong Custer, refused to command black regiments, even though it cost them promotions in rank. In addition, African Americans could only serve west of the Mississippi River, because many whites didn’t want to see armed black soldiers in or near their communities. And in areas where Buffalo Soldiers were stationed, they sometimes suffered deadly violence at the hands of civilians.

The Buffalo Soldiers’ main duty was to support the nation’s westward expansion by protecting settlers, building roads and other infrastructure, and guarding the U.S. mail. They served at a variety of posts in the Southwest and Great Plains, taking part in most of the military campaigns during the decades-long Indian Wars –– during which they compiled a distinguished record, with 18 Buffalo Soldiers awarded the Medal of Honor. This exceptional performance helped to overcome resistance to the idea of black Army officers, paving the way for the first African-American graduate from West Point Military Academy, Henry O. Flipper.

This article appears in its entirety at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture website. It can be read here.