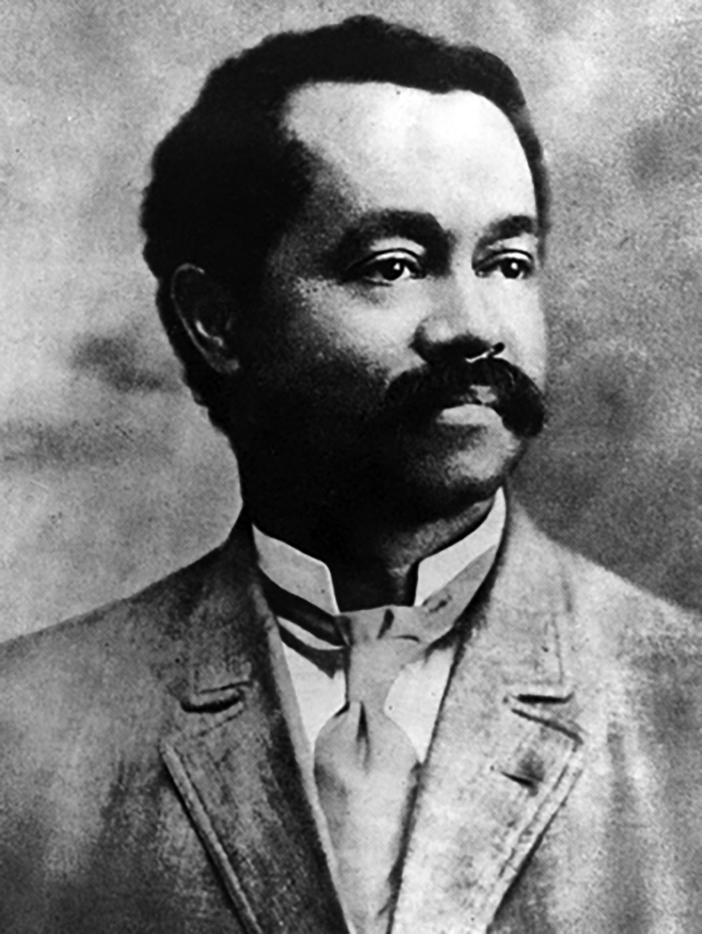

Systemic racism kept him from a position in higher education—but it didn’t stop Charles Henry Turner from rewriting our understanding of bees, ants, and cockroaches.

BY EDWARD D. MELILLO AUGUST 15, 2022

This story was originally published on The Conversation and appears here under a Creative Commons license.

ON A CRISP AUTUMN MORNING in 1908, an elegantly dressed African American man strode back and forth among the pin oaks, magnolias, and silver maples of O’Fallon Park in St. Louis, Missouri. After placing a dozen dishes filled with strawberry jam atop several picnic tables, biologist Charles Henry Turner retreated to a nearby bench, notebook and pencil at the ready.

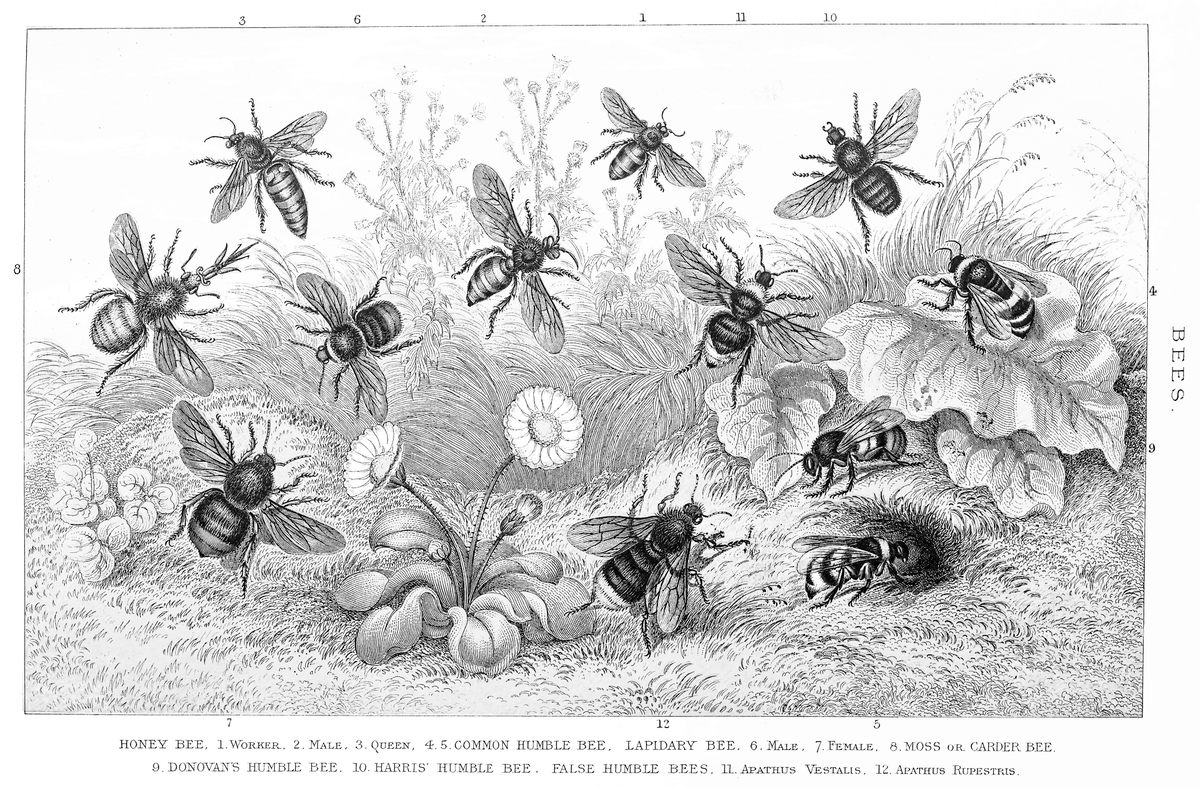

Following a midmorning break for tea and toast (topped with strawberry jam, of course), Turner returned to his outdoor experiment. At noon and again at dusk, he placed jam-filled dishes on the park tables. As he discovered, honeybees (Apis mellifera) were reliable breakfast, lunch, and dinner visitors to the sugary buffet. After a few days, Turner stopped offering jam at midday and sunset, and presented the treats only at dawn. Initially, the bees continued appearing at all three times. Soon, however, they changed their arrival patterns, visiting the picnic tables only in the mornings.

This simple but elegantly devised experiment led Turner to conclude that bees can perceive time and will rapidly develop new feeding habits in response to changing conditions. These results were among the first in a cascade of groundbreaking discoveries that Turner made about insect behavior.

Across his distinguished 33-year career, Turner authored 71 papers and was the first African American to have his research published in the prestigious journal Science. Although his name is barely known today, Charles Henry Turner was a pioneer in studying bees and should be considered among the great entomologists of the 19th and 20th centuries. While researching my book on human interactions with insects in world history, I became aware of Turner’s pioneering work on insect cognition, which constituted much of his groundbreaking research on animal behavior.

Turner was born in Cincinnati in 1867, a mere two years after the Civil War ended. The son of a church custodian and a nurse who was formerly enslaved, he grew up under the specter of Jim Crow—a set of formal laws and informal practices that relegated African Americans to second-class status.

The social environment of Turner’s childhood included school and housing segregation, frequent lynchings, and the denial of basic democratic rights to the city’s nonwhite population. Despite immense obstacles to his educational goals and professional aspirations, Turner’s tenacious spirit carried him through.

As a young boy, he developed an abiding fascination with small creatures, capturing and cataloging thousands of ants, beetles, and butterflies. An aptitude for science was just one of Turner’s many talents. At Gaines High School, he led his all-Black class, securing his place as valedictorian.

Turner went on to earn a Bachelor of Science degree from the University of Cincinnati, and he became the first African American to receive a doctorate in zoology from the University of Chicago. Turner’s cutting-edge doctoral dissertation, “The Homing of Ants: An Experimental Study of Ant Behavior,” was later excerpted in the September 1907 issue of the Journal of Comparative Neurology and Psychology.

Despite his brilliance, Turner was unable to secure long-term employment in higher education. The University of Chicago refused to offer him a job, and Booker T. Washington was too cash-strapped to hire him at the all-Black Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute in Alabama.

Following a brief stint at the University of Cincinnati and a temporary position at Clark College (now Clark Atlanta University), Turner spent the remainder of his career teaching at Sumner High School in St. Louis. As of 1908, his salary was a meager US$1,080 a year—around $34,300 in today’s dollars. At Sumner, without access to a fully equipped laboratory, a research library, or graduate students, Turner made trailblazing discoveries about insect behavior.

Among Turner’s most significant findings was that wasps, bees, sawflies and ants—members of the Hymenoptera order—are not simply primitive automatons, as so many of his contemporaries thought. Instead, they are organisms with the capacities to remember, learn, and feel.

During the early 1900s, biologists were aware that flowers attracted bee pollinators by producing certain scents. However, these researchers knew next to nothing about the visual aspects of such attractions, when bees were too far from the flowers to smell them.

To investigate, Turner pounded rows of wooden dowels into the O’Fallon Park lawn. Atop each rod, he affixed a red disk dipped in honey. Soon, bees began traveling from far away to his makeshift “flowers.”

Turner then added a series of “control” rods topped with blue disks that bore no honey. The bees paid little heed to the new “flowers,” demonstrating that visual signals provided guidance when the bees were too distant to smell their targets. Although a honeybee’s ability to detect red remains controversial, scientists have determined that Turner’s bees were likely responding to something called achromatic stimuli, which allowed them to discern among various shades and tints.

Turner’s astounding range of findings from three decades of experiments established his reputation as an authority on the behavioral patterns of bees, cockroaches, spiders, and ants.

Alongside his scientific publications, Turner wrote extensively on African American education.

As a scientific researcher without a university position, he occupied an odd niche. In large part, his situation was the product of systemic racism. It was also a result of his commitment to training young Black students in science.

Alongside his scientific publications, Turner wrote extensively on African American education. In his 1902 essay “Will the Education of the Negro Solve the Race Problem?” Turner contended that trade schools were not the pathway to Black empowerment. Instead, he called for widespread public education of African Americans in all subjects: “if we cast aside our prejudices and try the highest education upon both white and Black, in a few decades there will be no Negro problem.”

Turner was only 56 when he died of acute myocarditis, an infectious heart inflammation. He was survived by two children and his second wife, Lillian Porter.

Turner’s scientific contributions endure. His articles continue to be widely cited, and entomologists have subsequently verified most of his conclusions.

Despite the colossal challenges he faced throughout his career, Charles Henry Turner was among the first scientists to shed light on the secret lives of bees, the winged pollinators that ensure the welfare of human food systems and the survival of Earth’s biosphere.

Edward D. Melillo is a professor of history and environmental studies at Amherst College.