While slavery was undoubtedly the engine of this discord, there were other gears grinding in the background—less visible, perhaps, but no less significant. Among them: tariffs and taxes. In this post, we take a long look—calmly and plainly—at how economic policy, particularly the contentious issue of tariffs, both reflected and exacerbated the deeper divisions of a fractured America. Slavery was the spark, but tariffs helped stack the kindling.

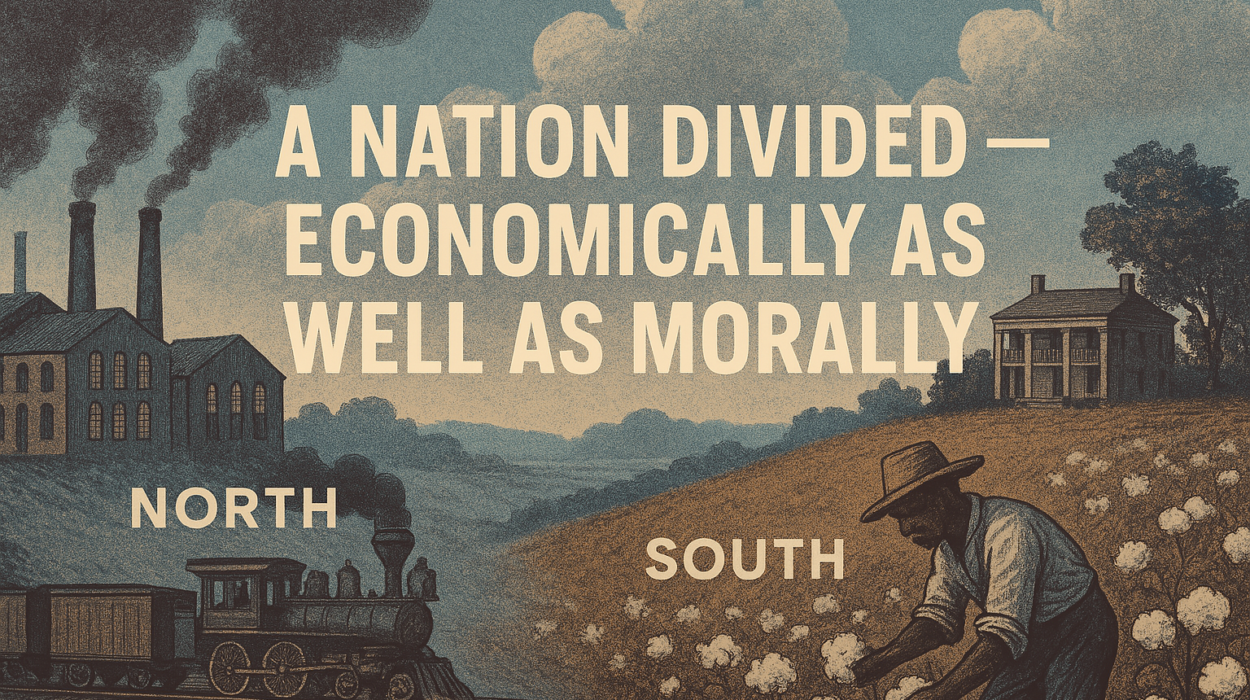

A Nation Divided — Economically as Well as Morally

In the early 1800s, the United States was already a land of two destinies. A bustling industrial economy in the North took root, fueled by innovation, immigration, and mechanization. In the South, the land was king. The economy rested squarely on agriculture—cotton, tobacco, and rice—and that economy, in turn, rested on the back of slavery.

These divergent paths sowed the seeds for more than moral disagreement. They created two regions that looked at the same policies—particularly federal tariffs—through radically different lenses.

A tariff, in plain terms, is a tax on imported goods. For the North, it meant protection—a shield for its nascent industries against British and French competition. For the South, it was a burden—a penalty on the foreign goods they purchased and a barrier to selling their own cotton abroad.

And there lay the crux of the matter.

The Tariff of Abominations and the Southern Backlash

In 1828, Congress passed what came to be known in the South as the “Tariff of Abominations.” It raised duties on imported manufactured goods to record highs. Northern manufacturers rejoiced. Southern planters seethed.

South Carolina led the charge in resistance. Its most vocal champion was then-Vice President John C. Calhoun, who anonymously authored the “South Carolina Exposition and Protest,” arguing that states had the right to nullify federal laws deemed unconstitutional. This doctrine of nullification became a rallying cry—not just against tariffs, but eventually against federal interference with slavery itself.

What followed in 1832 was the Nullification Crisis. South Carolina declared the tariffs of 1828 and 1832 null and void. President Andrew Jackson, no stranger to a duel or a stare-down, threatened military action. Cooler heads prevailed with a compromise tariff, but the stage had been set. The tension between federal authority and states’ rights had become a matter not just of policy, but of principle.

Yet, the crisis revealed something more: that the South was willing to consider extreme measures to preserve what it saw as its economic freedom—and later, its social and racial order.

The Economics of Sectionalism

By the 1850s, the South was producing roughly 75% of the world’s cotton—its exports critical not just to Southern prosperity but also to British and French textile industries. Yet that wealth was not reinvested into railroads, factories, or urban infrastructure as it was in the North. Instead, it was invested in land and, most grimly, in slaves.

The Southern economy depended on free labor—enslaved labor. As long as cotton remained profitable, there was little incentive to industrialize or to support protective tariffs. In fact, Southerners preferred low tariffs to keep foreign markets open to their exports and to keep the cost of imported goods low.

Contrast this with the North, where protective tariffs helped steel, textiles, and machinery industries flourish. Northerners viewed the federal government as a vehicle for national improvement—funding canals, railroads, and westward expansion. To the South, that same federal power was increasingly seen as a threat—economic, political, and ultimately existential.

Taxes, Tariffs, and the Fear of the Future

By the 1850s, the debates around tariffs had become deeply entangled with the broader argument over slavery. The South feared a future in which a Northern-dominated Congress might use federal power—including economic tools like taxation—to reshape the Southern way of life.

While there was no federal income tax at the time, tariffs made up the bulk of government revenue. Southerners believed—rightly, to a degree—that they bore a disproportionate share of that burden. After all, they imported more, and thus paid more duties.

Northern leaders, particularly in the Republican Party, were hardly unaware of this. They supported a national economic model that used tariff revenue to fund infrastructure and growth. Southern leaders, on the other hand, viewed such policies as a redistribution of Southern wealth to Northern interests.

It’s no accident that when the Confederate States of America formed in 1861, their constitution not only preserved slavery—it also outlawed protective tariffs. Their grievances, while centered on slavery, included a deep resentment toward what they saw as an economically exploitative federal government.

The Election of Lincoln and the Breaking Point

When Abraham Lincoln won the presidency in 1860 without carrying a single Southern state, the response was swift. South Carolina seceded in December, and within months, ten other states followed.

Though slavery was the heart of the matter, economic grievances were prominent in secession documents. South Carolina’s declaration accused the North of imposing “unequal burdens” through tariffs and using Southern wealth to fund Northern growth.

They feared not just abolition, but economic subjugation—an end to their way of life, both socially and fiscally. The election of a president who opposed the expansion of slavery confirmed their worst suspicions: that they were now a permanent minority in a nation with a different moral compass and economic agenda.

War and the Legacy of Economic Division

When war came in 1861, it came clothed in the language of union and liberty, but it was stitched with threads of economic division.

During the war, both sides enacted new economic policies. The Union introduced the first federal income tax in 1861 and passed the Morrill Tariff, which raised duties to fund the war and further protect industry. The Confederacy struggled to raise funds without tariffs, relying heavily on printing money, which led to catastrophic inflation.

In the end, it was not just bullets and bayonets that determined the outcome—it was also economic endurance. The industrialized North outproduced the agrarian South in nearly every category—iron, arms, textiles, and manpower. The very federal government the South had opposed became a wartime engine too powerful to resist.

Conclusion: The Tangled Web of Conflict

So, what are we to make of it? Did tariffs cause the Civil War? No, not directly. But they mattered.

Tariffs and taxes were the economic language of a deeper conflict—a struggle over power, identity, and destiny. They exposed the profound differences between two Americas: one moving toward industry, wage labor, and national unity, and the other rooted in agriculture, slave labor, and state sovereignty.

The debate over tariffs reflects the broader anxieties of a nation unsure of its future. The refusal to compromise on either slavery or economics shows how political inflexibility can rupture a fragile peace.

And that is the way it was—

America was torn not just by what it believed but also by how it lived, worked, and profited. It was a house divided not only on moral grounds but also on the balance sheets of its regions.

History, like journalism, is a search for the whole story. Tariffs may seem the stuff of dull textbooks and dry legislation. But in this case, they played a supporting role in one of history’s great tragedies.

And that… is the way it was.

References:

“Tariffs and the American Civil War” – Essential Civil War Curriculum.

“The Economics of the Civil War” – EH.net – A deep dive into economic factors, including slavery and tariffs.

“The Problem of the Tariff in American Economic History” – Cato Institute – A broader look at tariff policy and its national effects.