This is a story of a community pushed to the margins but determined to forge its path to prosperity and dignity.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, African Americans faced systemic exclusion from the economic lifeblood of the nation. White-dominated banks, insurance companies, and fraternal organizations routinely shut their doors to Black customers. This wasn’t just casual neglect, it was deliberate, codified discrimination. Faced with these barriers, African Americans turned inward, building institutions that would serve their communities. Thus began the rise of Black-owned banks and fraternal organizations, symbols of self-reliance and hope in the shadow of Jim Crow.

Systemic Exclusion and the Birth of Self-Reliance

When mainstream financial institutions refused to serve Black customers, the response was practical and profound: build their own. This exclusion wasn’t just an inconvenience. It was a catalyst. The Black self-help movement emerged, emphasizing financial independence, mutual support, and community-driven progress. Organizations like the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows, the Colored Knights of Pythias, and the Improved Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks of the World rose to meet needs that white institutions ignored.

These were more than just social clubs; they were lifelines. They provided insurance, burial benefits, and even healthcare at a time when such services were otherwise inaccessible. They were, in every sense, a foundation for survival and growth.

The Emergence of Black-Owned Banks

Financial independence found its strongest footing with the establishment of Black-owned banks. Capital Savings Bank, founded in Washington, D.C., in 1888, was one of the first. It symbolized Black self-determination at a time when financial autonomy was both rare and revolutionary. Frederick Douglass was involved, lending his voice and stature to the cause. The bank offered savings accounts, loans, and financial advice, providing a crucial service denied by mainstream banks.

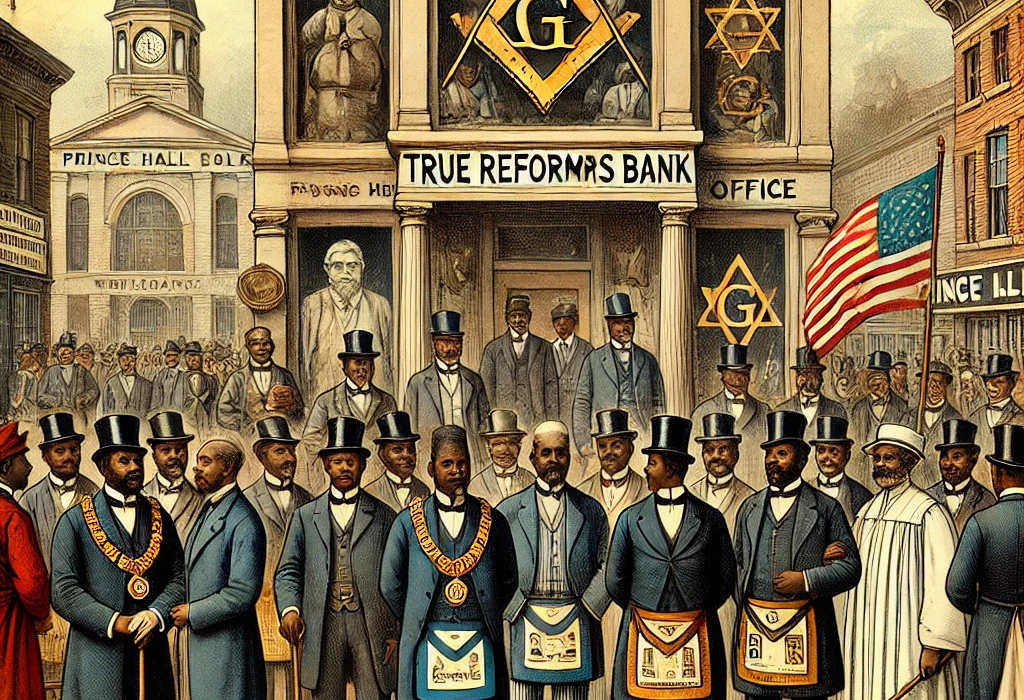

That same year, the True Reformers Bank opened its doors in Richmond, Virginia. Founded by the Order of the True Reformers, it became the first Black-owned bank chartered and independently operated by African Americans. It helped Black families buy homes, fund businesses, and invest in their future. These institutions weren’t just banks but symbols of a community refusing to be sidelined.

While some of these banks, like Capital Savings, faced financial hardships and short lifespans, they laid the groundwork for future Black financial institutions. They were beacons of progress in a society rife with systemic barriers.

The Vital Role of Fraternal and Mutual Aid Organizations

Fraternal organizations were engines of economic empowerment. Groups like the Order of the True Reformers, the Prince Hall Freemasons, and the Mosaic Templars of America blended mutual aid with business acumen. They offered life insurance, educational scholarships, and even healthcare services, stepping in where the government and private sector had failed.

The Order of the True Reformers, for instance, provided life insurance to African Americans when white-owned companies refused. They didn’t stop there; they ventured into real estate and publishing and even ran a retirement home. These organizations created jobs, fostered pride, and instilled a sense of economic self-sufficiency.

These fraternal orders were also incubators for leadership. They nurtured individuals who later became pivotal figures in the civil rights movement. They provided a space where African Americans could hone their skills, develop networks, and strategize for broader social change.

Economic Empowerment as a Pathway to Social Advancement

The connection between economic independence and social equality was clear to the Black community. These organizations promoted education, entrepreneurship, and racial uplift, recognizing that financial stability was a cornerstone of broader societal advancement.

The Colored Farmers Alliance is a prime example. This group organized Black farmers to demand better wages, fair pricing, and cooperative farming practices. By addressing economic injustices directly, they fortified their communities against the pervasive racial discrimination and violence of the time.

Collectively, these efforts created a network of support that sustained African American communities through some of the darkest periods in American history. They provided financial services, hope, and a vision for a better future.

Challenges and Limitations

But the road was not without its bumps. Many of these institutions faced significant challenges. Economic downturns, mismanagement, and the persistent weight of systemic racism took their toll. The True Reformers Bank, despite its early successes, collapsed in 1910, leading to the decline of the organization. Capital Savings Bank faced similar difficulties.

Rapid expansion often outpaced managerial capacity, and in many cases, the economic realities of the time proved too harsh to overcome. Yet, even in failure, these institutions left a lasting mark.

A Legacy That Endures

Despite their struggles, the legacy of these early efforts is undeniable. They laid the groundwork for future movements and institutions dedicated to African American progress, from the NAACP to the Urban League and eventually the Civil Rights Movement of the mid-20th century.

The creation of Black-owned banks and fraternal organizations reinforced the importance of economic empowerment in the fight for civil rights. They demonstrated that African-American-led institutions could succeed, even under the oppressive conditions of segregation. They inspired future generations of entrepreneurs, leaders, and activists, proving that self-reliance and community support could be powerful tools for change.

Consider the Mosaic Templars of America, founded in 1883 Little Rock, Arkansas. They operated a bank, a publishing house, and even a hospital, extending their reach as far as the Caribbean and South America. The Prince Hall Freemasons, established in 1784, were among the earliest fraternal organizations for African Americans, promoting education, philanthropy, and civil rights advocacy.

Conclusion

Establishing Black-owned banks and fraternal organizations during the post-Reconstruction era was more than an economic endeavor. It was an act of resistance and resilience. These institutions provided vital services, fostered leadership, and cultivated economic self-determination in a society that excluded them.

Referenced: African American Registry, Black Past, Encyclopedia Virginia, Attucks Adam Washington. DC