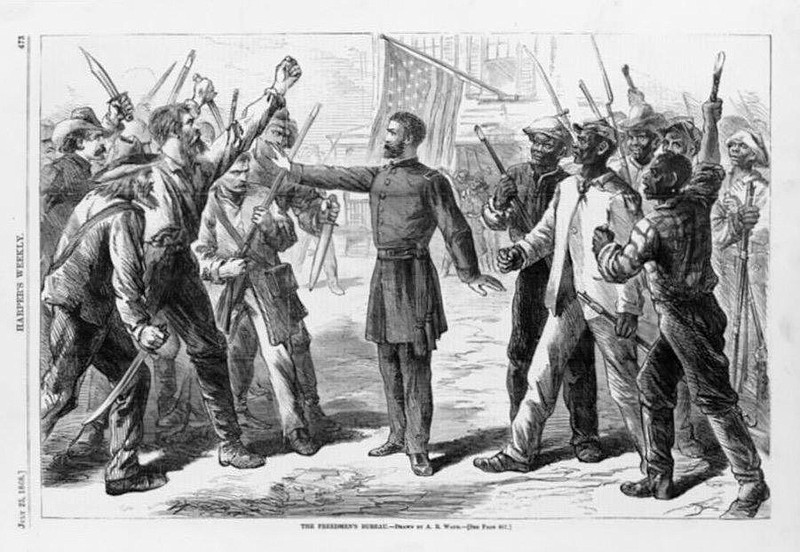

Establishment

The Freedmen’s Bureau was established on March 3, 1865. It was officially known as the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands. Congress created it during the closing months of the American Civil War to assist formerly enslaved African Americans and other war refugees in the Southern states.

Key members

The Freedmen’s Bureau employed around 900 to 1,000 agents at its peak. These agents were responsible for overseeing various tasks such as distributing food, managing labor contracts, providing education, and more. Key members among them were:

Reverend Richard H. Cain was a minister and politician who advocated for civil rights and worked with the Bureau in South Carolina.

Martin R. Delany, an abolitionist and the first African American field officer in the U.S. Army, served as a Bureau official in South Carolina.

John Mercer Langston**, one of the first African Americans elected to public office in the United States, was heavily involved in the Bureau’s educational efforts.

General Oliver O. Howard was the head of the Freedmen’s Bureau. Howard, a Union general during the Civil War, oversaw the Bureau’s activities. Howard University in Washington, D.C., is named after him.

General Rufus Saxton: Oversaw operations in South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida.

General John Eaton: He was in charge of operations in Tennessee.

General Clinton B. Fisk: He led the Bureau’s efforts in Kentucky and Tennessee, and Fisk University is named after him

Administrative opposition

The Freedmen’s Bureau encountered significant opposition, primarily from President Andrew Johnson and subsequent administrations. This opposition severely hindered the Bureau’s mission to provide support and protection for African Americans during the turbulent Reconstruction era.

President Johnson’s opposition was evident in his veto of the Freedmen’s Bureau Bill 1866. This bill sought to extend the Bureau’s life and broaden its powers to assist the freedmen better. Although Congress managed to override Johnson’s veto, the act indicated his resistance to the Bureau’s goals. Johnson’s policies further obstructed the Bureau’s efforts by granting pardons to former Confederate landowners. These pardons restored property rights to those who had supported the Confederacy, meaning that land intended for redistribution to African Americans was instead returned to its former owners. This action undermined efforts to establish economic independence for freedmen and left many African Americans without the land they had been promised.

In addition to vetoing the Freedmen’s Bureau Bill, Johnson also opposed the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which aimed to protect the rights of African Americans, including those overseen by the Freedmen’s Bureau. His opposition weakened the enforcement of civil rights protections, as his administration provided little support for enforcing the Bureau’s policies. This lack of federal backing was particularly damaging in the face of Southern resistance, making it difficult for the Bureau to maintain its authority and protect African Americans from exploitation and violence.

Johnson’s decision to reduce the federal military presence in the South further weakened the Freedmen’s Bureau. Without sufficient military support, Bureau agents were often powerless to intervene in acts of racial violence or to enforce policies effectively. Groups like the Ku Klux Klan took advantage of this, using violence and intimidation to undermine the Bureau’s efforts and maintain white supremacy in the South.

Moreover, Johnson, a Southern Democrat, sympathized more with the plight of Southern whites than with the newly freed African Americans. His administration’s policies often reflected a desire to restore the Southern states to their pre-war status, which included limiting the rights and freedoms of African Americans. This ideological stance further impeded the Bureau’s work, as policies were implemented that were at odds with the Bureau’s mission.

Positive works

Despite its many shortcomings, the Freedmen’s Bureau made notable lasting contributions, particularly in education, healthcare, and legal assistance. These efforts, though limited, laid the groundwork for improvements in the lives of African Americans at a critical juncture in American history.

One of the Freedmen’s Bureau’s most significant achievements was establishing education for African Americans. The Bureau was instrumental in creating thousands of schools across the South, providing access to education for those who had been denied it during slavery. It also supported founding historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs), such as Howard University and Fisk University. These institutions continue to play a crucial role in the education and empowerment of African Americans to this day.

The Freedmen’s Bureau made strides in healthcare by establishing hospitals and providing much-needed medical care to African Americans. Many of the newly freed individuals suffered from diseases and injuries stemming from the brutal conditions of slavery and the Civil War. Though under-resourced, the Bureau’s medical division was one of the first large-scale government efforts to address the health needs of African Americans, treating tens of thousands during its operation.

Legal assistance was another area where the Bureau made an impact. In a post-slavery society, navigating the new legal landscape was challenging for African Americans. The Bureau’s agents helped formalize marriages that had been denied legal recognition under slavery and assisted in disputes over labor contracts. They also worked to protect African Americans from exploitation by employers and landowners, though their success varied.

The Bureau also provided crucial support during the transition from slavery to freedom. It offered food, clothing, and temporary shelter to freedmen and displaced persons, which was vital in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War when many African Americans faced extreme poverty and displacement.

Culturally and socially, the Freedmen’s Bureau helped foster a sense of community and identity among freedmen by supporting churches, social organizations, and community gatherings. These institutions became vital centers for African American culture, social life, and political organization during and after Reconstruction.

The lack of support for continuing the Freedmen’s Bureau led to its early termination in 1872, just seven years after its establishment.

Reference: Encyclopedia.com, Wikipedia, Britannica, Khan Academy